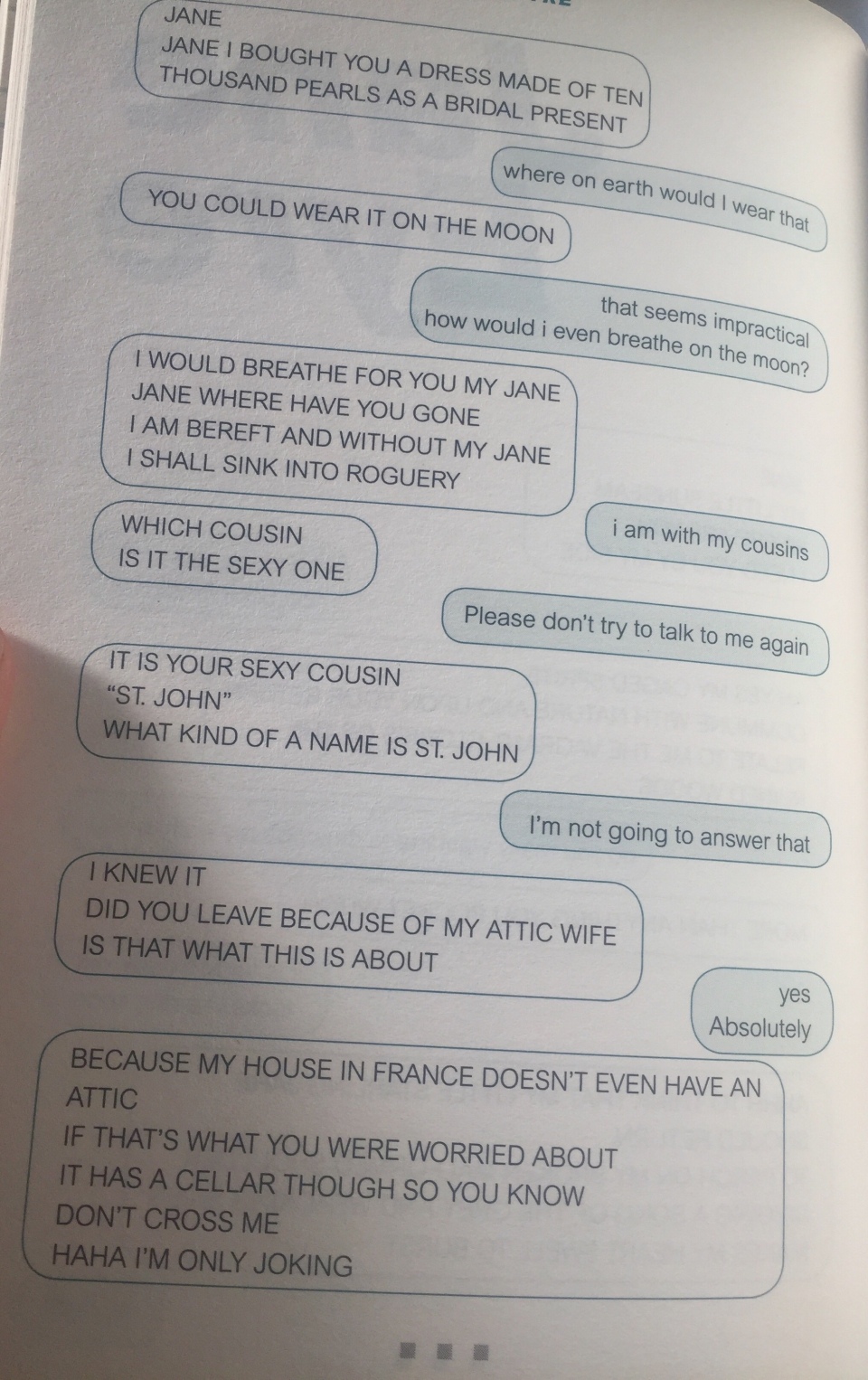

Texts from Jane Eyre…

https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:463653/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Some critics suggest that Stella takes no side in the conflict between Blanche and Stanley – how far do you agree?

The symbolic meaning of Jane’s art…

The first major use of art within Jane Eyre is when Jane presents her watercolours to Rochester upon their first meeting at Thornfield.

The first represented clouds low and livid, . . . there was no land. One gleam of light lifted into relief a half-submerged mast, on which sat a cormorant, dark and large, with wings flecked with foam; its beak held a gold bracelet, set with gems, . . . . Sinking below the bird and the mast, a drowned corse glanced through the green water; a fair arm was the only limb visible, whence the bracelet had been washed or torn.

The “presentiment” of the images was likely Brontë’s intention in their inclusion, the first one especially: the cormorant in the image is “dark and large” and “flecked with foam”, prefiguring the racially-tinged origin of Bertha Mason in the Carribean, her imposing size, and, with the alliance of foam with rabies and madness, her own insanity, and it steals from the “fair arm” a golden bracelet studded with gems — or, perhaps, a wedding band, symbolising the first marriage ceremony between Jane and Rochester. The sudden announcement of Rochester’s bigamist relationship to Bertha snatches away the wedding band that should have been on Jane’s finger, instead returning it to Bertha, and leaving Jane to drown in her emotions before fleeing Thornfield. Barbara Gates takes a slightly different approach to interpreting the image, associating Rochester with the bird, but both interpretations assume it refers to the same incident.

The second picture contained for foreground only the dim peak of a hill, with grass and some leaves slanting as if by a breeze. . . . rising into the sky was a woman’s shape to the bust, portrayed in tints as dusk and soft as I could combine. The dim forehead was crowned with a star; . . . the eyes shone dark and wild; the hair streamed shadowy. . . . On the neck lay a pale reflection like moonlight; the same faint lustre touched the train of thin clouds from which rose and bowed this vision of the Evening Star.

The second image prefigures Jane’s wanderings in Whitcross, specifically her final approach to the Moor House of the Rivers’. “The woman in the drawing, with her streaming hair, dark, wild eyes and pale neck, strongly resembles Jane, who is drenched, wild-eyed, and pale as a ‘spectre’ when found by the Rivers”. It is worth noting, as well, that the star is perched at the very top of the forehead, a position endowed with mythological importance in many eastern religions and pagan beliefs.

The third showed the pinnacle of an iceberg piercing a polar winter sky: a muster of northern lights . . . along the horizon. Throwing these into distance, rose, in the foreground, a head. . . . Two thin hands, joined under the forehead, . . . a brow quite bloodless, white as bone, and an eye hollow and fixed, blank of meaning but for the glassiness of despair, alone were visible. Above the temples, . . . gleamed a ring of white flame, gemmed with sparkles of a more lurid tinge. This pale crescent was “the likeness of a Kingly Crown;” what it diademed was “the shape which shape had none.”

The third image is a strong reference to St. John, described when Jane meets him as having a “high forehead, colourless as ivory, [and] partially streaked over by careless locks of fair hair”. The quotation at the end of the description, however, complicates the parallel somewhat; the footnote to the Broadview edition notes the quote is from Milton’s description of Death within Paradise Lost . St. John is both a narcissist and a martyr, and one of the manners in which that expresses itself is in his sermon’s emphasis on death and damnation. Additionally, Jane quotes Diana Rivers as calling St. John “‘As inexorable as death,'” and she agrees . Lawrence Moser, on the other hand, sees Jane’s previous experiences at Lowood in the watercolour, writing that “the inspiration was most probably founded in Miss Temple’s departure from Lowood. . . an absence that drew a veil, so to speak, over the temporarily happy Jane. The crown, again the only point of light in the portrait . . . symbolizes her affectionate heart and its love”. That the face is not assigned a gender makes both readings plausible, and it may very well stand for both of them, as symbols of the larger Church and Christian faith.

Moser also calls these images as “surrealistic,” a description that appears to be slightly over-eager; as compared to the works of the committed surrealists of the 20th century such as Duchamp and Dali, Jane Eyre’s images are relatively well-mannered. The surreality of these images is somewhat besides the point, however; the genre did not exist at the time, and to imagine them as existing within the continuum of surreal art is anachronistic in the extreme. Jane Millgate, while agreeing with Moser about the images’ surreal nature, points out that “even though Rochester is impressed by their being ‘for a school girl, peculiar’, the reader finds their portentousness, lack of originality, and naivety somewhat embarrassing — and this cannot be dismissed as simply a modern reaction”. They are somewhat quaint, even in their oddity; the descriptions allow for no nuance in the images themselves, and they appear didactic and simplistic in their application of symbolism — the vast, glacial forehead, the mingling of the outline of the individual with the stars: these visual cliches persist even today.

Why are these images in the text, aside from rounding out Jane’s character with other lady-like skills? None of the other images she creates in the text are anything like these — all portraits and conventional landscapes — or described in such detail. The answer lies not so much in the images themselves but the conversation which follows their presentation to Rochester.

“And you felt self-satisfied with the result of your ardent labours?”

“Far from it. I was tormented by the contrast between my idea and my handiwork: in each case I had imagined something which I was quite powerless to realize.”

It is hard not to read autobiography into these lines, or at least strong authorial intent and comment. The gulf between what an artist intends to create with art and what they actually manage to create is something with which anyone involved in creative work is familiar. These images, for all their faults and their odd surreal nature, are but shadows of their true nature; the metaphor can be telescoped upward, with Brontë commenting on her own creative process, as both a literary outsider and a woman, who had faced rejection by publishers before the eventual acceptance of Jane Eyre.

Sandra Gilbert, taking a different tack, mentions that the paintings in the text also allow for Rochester and Jane to appear as equals within the novel. Though such talk would bewilder Rochester’s other dependants, it is a breath of life to Jane, who begins to fall in love with him not because he is her master but in spite of the fact that he is, not because he is princely in manner but because, being in some sense her equal, he is the only entitled critic of her art and her soul. This sense that Jane is using the images she creates to attempt to position herself relative to Rochester on the social ladder of Victorian society is reinforced with her paired portraits of herself and Blanche Ingram. “It does good to no woman to be flattered by her superior, who cannot possibly intend to marry her; and it is madness in all women to let a secret love kindle within them, which, if unreturned and unknown, must devour the life that feeds it,” she tells herself as she sets out to create the doubled images.

The doubling in this sequence appears to be a direct refutation of the philosophy that Gilbert sees in the watercolour segment — whereas those images set out to allow Rochester and Jane to be equals, these images are created to set Jane as lower and less worthy of Rochester than Blanche. She paints Blanche from Mrs. Fairfax’s physical description of her, and draws her own self-portrait from a small mirror. Blanche’s is done up in the finest paints Jane can muster, and is almost homoerotic in tone at points, in her description of Blanche’s beauty — or as impassioned as Jane will allow herself to become, at any rate. “Recall the august yet harmonious lineaments, the Grecian neck and bust: let the round and dazzling arm be visible, and the delicate hand”. Jane, here, strives to draw Blanche as if Jane were looking at her from the position of a male: hijacking the male gaze of Rochester to attempt to batten down her own hopes that Rochester is gazing at her instead.

However, the emphasis on the physical of these images gives away their falsehood. Rochester’s interest in Jane is not physical, but instead rooted in her fiery will and personality. Jane’s expectation is that Blanche’s various material qualities would automatically drive Rochester to prefer her over Jane, but, instead, he describes her as the real beauty. “‘You are a beauty, in my eyes; and a beauty just after the desire of my heart'”. Although Rochester is looking at Jane with the same gaze that she attempted to use to create her portrait of Blanche, he sees something very different than just her “Quakerish” physical plain-ness. Rochester makes his distrust of the outward appearance of women plain on the following page: “‘To women who please me only by their faces, I am the very devil when I find out they have neither souls nor hearts . . . but to the clear eye and the eloquent tongue, to the soul made of fire . . . I am ever tender and true'”. This is an admission of love which is made just for Jane, to whom fire imagery clings to throughout the novel.

The final major artistic moment within the text occurs during Jane’s exile at the Moor House, and her employment at the school there. The undercurrent of homoeroticism that had been visible in Jane’s desire to create a portrait of Blanche Ingram resurfaces here: “I felt the thrill of artist-delight at the idea of copying from so perfect and radiant a model . . . I promised myself the pleasure of colouring it. . .”. This strong of a reaction to her presence, even after she had dismissed Miss Rosamond as “not profoundly interesting or thoroughly impressive” just a few paragraphs before.

“St. John is a finely-observed study of a man who turns egoism and ambition to the service of religion,” pronounces Craik. “He is indeed not attractive himself, and all his speeches are about, or soon turn to, himself”. However, his narcissism does not preclude him from lusting after Miss Rosamond, even if he will not allow himself the pleasure of acting out his physical desires. “Even his passion for the elementary Miss Oliver indicates his deficiency, in caring in such as way for a woman so clearly inferiors to what he has been accustomed to in his sisters, apart from Jane herself”

It is the image of Miss Rosamond which changes the relationship between Jane and St. John dramatically; not only does it provide him with her real name, and set the plot moving forward once more, but it allows for Jane — and the reader — to plumb the depths of St. John’s character. He attempts to avoid her, to begin with, with facile compliments: “‘A well-executed picture,’ he said; ‘very soft, clear colouring,'” but Jane is having none of it. Here, the question of gaze returns to the text. “He continued to gaze at the picture: the longer he looked, the firmer he held it, the more he seemed to covet it” . It is this somewhat innocuous, seemingly throwaway line that St. John’s character and attitude toward women is collected together for the reader — he covets what he remains close to, and wishes to control it. He does not chase after Jane at first, either, but instead grows to the idea of her accompanying him to the colonies on his missionary work as she becomes familiar to him. A woman is not an individual to St. John, but a worldly bauble to alternatively covet and deny, and entirely physical, as evidenced by his two-faced desire for and rejection of Miss Rosamond at this juncture, and his proposal of a loveless marriage to Jane later on in the section. Women are merely temporary distractions in this world, alternatively aiding in achieving the paradise of the next world or leading him astray, never individuals in their own rights — mirroring the position that the Church itself took toward women at this time, a fact of life that Charlotte Brontë, the daughter of a preacher, would have been fully aware of.

Careful examination of the art within Jane Eyre, then, leads to a greater understanding of how the text functions as a whole, and how Brontë intended the characters and events within the text to function as critiques of society. The watercolours presented by Jane to Rochester at their initial meeting at Thornfield act as both foreshadwing for other events in the book, predicting the disastrous initial marriage to Rochester, Jane’s homelessness prior to entering Moor House, and her subsequent acquaintance with St. John, as well as represent a broader point about art and the impossible task of the artist to faithfully represent their vision in whatever medium they’re working in. The doubled portraits of Jane Eyre and Blanche Ingram emphasize the physical and social differences between the two of them, and appear to denigrate Jane. However, Rochester once again demolishes this emphasis on the external, instead telling Jane he loves her for her will, mind, and spirit. St. John, on the other hand, has his rejection of these same characteristics revealed with his reaction to Jane’s portrait of Miss Rosamond, and his physical lust for her, tempered by his eventual request for Jane herself to accompany him to India — showing that he considered them almost interchangeable and only in the light of his own needs, and not individuals. The varieties of use of art within Jane Eyre, then, emphasize that Charlotte Brontë intended for there to be various shades of meaning to the work, and that, far from being an exercise in redundancy, approaching the work from a variety of theoretical positions allows for a deeper, fuller, and more rewarding of the text as a whole.

Central themes and contextual links in ‘A Streetcar named Desire’.

Desire and Fate: This is a dominant theme that runs throughout the play and is particularly prominent in the title itself. Williams himself was intrigued by the names of two streetcars that carried the words ‘Desire’ and ‘Cemeteries’ as their destination. Whilst living in New Orleans in 1946 Williams mentioned these aptly named streetcars in an essay he wrote: Their indistinguishable progress up and down Royal Street struck me as having symbolic bearing of a broad nature on the life in the Vieux Carre – and everywhere else for that matter.’

A streetcar running directly to its destination on a predetermined course could easily be seen as a symbol of fate. For Williams, however, the streetcar’s destination, ‘Desire’, spoke more than an undefined force of fate. This force clearly drives Blanche, her sexual passion and desire overwhelms her at moments in the play, we see her clearly driven by forces more powerful than her. She acknowledges Stanley’s masculinity and animal passion from the onset of her visit. She openly flirts with him and teases (not necessarily in a sexual way always, but she often seeks a reaction or attention) him as the play develops.

The image of the streetcar is used in scene 4 when Stella and Blanche discuss sexual desire. Stella asks Blanche, ‘Haven’t you ever ridden that streetcar?’ Stella is clearly a passionate woman too, perhaps driven by the same force as Blanche. She did after all abandon her life on a country plantation and succumb to the passionate love of Stanely. Is the final destination for Stella shown in Eunice perhaps?

There is another image of fate in the play. In scene 4, 6 and 10 Williams introduce a roaring locomotive at a dramatic moment: Blanche’s condemnation of Stanley; her description of her husband’s death and just before the rape. However, the random introduction of the locomotive as a symbol of fate does not carry here the impact of the streetcar metaphor. It could be that Williams had originally intended the locomotive as the leitmotiv (dominant, or lead, motif) of his play, but considered the ironic predetermined course of a lurching streetcar to be far more dramatic.

The idea that Williams is trying to convey seems to be that to be drive by desire is self destructive, yet the victims of an overpowering passion are carried along helplessly, unable to escape. Blanche’s fate is preordained, this is not only stressed in the streetcar image but several key moments in the play indicate that there cannot be a happy conclusion to Blanche’s story. The incident with the ‘young man’ collecting money and her elusive and dishonest drinking reveal the uncontrollable forces that drive her. Throughout his life Tennessee Williams was driven from one sexual encounter to another, exactly like Blanche, and like Blanche he too seemed incapable of committing himself to a permanent relationship, in his case homosexual. When Blanche longs for Mitch to marry her, she is not seeking a permanent sexual relationship but the material security of a home of her own (‘The poor man’s Paradise — is a little peace’ — Scene 9).

Death:Images of death recur throughout the play. The streetcar going to ‘cemeteries’ is another reminder from Williams of the likely eventual outcome of a life driven by passion and serves to reinforce the theme of fatal desire.

The references that Blanche makes to caring for her dying relatives at Belle Reve remind us of the strength she once must have had and the horrors that she witnessed. The woman swollen by disease and unable to fit into a coffin and then ‘burned like rubbish’ and the ‘blood stained pillow-slips’ then later Blanche’s wish to be ‘buried at sea sewn up in a clean white sack’ all provide chilling reminders of the life Blanche has left behind physically but not mentally. When Blanche comments that she didn’t speak about death in her conversations with the dying we see how he probably never let herself grieve, especially for her dead husband.

The suicide of Blanche’s young husband is significant throughout the play. It’s own polka music reminds us insistently of the tragedy. The music in Blanche’s mind haunts her and grows louder until the fatal echo of the gunshot stops it. The disgust she openly showed at her husband’s homosexuality and her guilt at his subsequent suicide partly accounts for mental instability, her promiscuity and her alcoholism.

Madness: Blanche’s fear of madness is first hinted at in Scene 1 (‘I can’t be alone! Because — as you must have noticed — I’m — not very well …‘). Never stable even as a girl, she was shattered by her husband’s suicide and the circumstances surrounding it. Later the harrowing deaths at Belle Reve with which she evidently had to cope on her own, also took their toll. By this time she had begun her descent into promiscuity and alcoholism, and in order to blot out the ugliness of her life she created her fantasy world of adoring respectful admirers, of romantic songs and gay parties.

She is never entirely successful at this, as the memories of her husband’s suicide remain persistently alive in her mind, always accompanied by the polka music. Drink is her solace on these occasions as she waits for the sound of the shot that signals the end of the nightmare. It seems that she has learned to live with this, as she remarks to Mitch in a matter-of-fact way, ‘There now, the shot! It always stops after that!’ (Scene 9).

She has reached an accommodation with the nightmares in her mind, but she cannot bear the intrusion of ugly reality into her make-believe world. Stanley’s revelations of her past, Mitch’s rejection of her as ‘not clean enough’ and his clumsy attempt at raping her, and finally her rape by Stanley on the night when her sister is giving birth to his child, all these break her and her mind gives way. She retreats into her make-believe world, making her committal to an institution inevitable.

Like the other major themes of the play – desire and fate, and death – madness too was Tennessee ‘Williams’s obsession. His sister Rose’s strange behaviour which had long been a source of anxiety to her parents, later took the form of violent sexual fantasies and accusations against her father. Her parents had her committed to an institution. Following the medical practice of the time a pre-frontal lobotomy was carried out, and Rose calmed down, certainly, but was left with no memories, no mind. Not only did Tennessee Williams feel guilty for not having saved Rose from all this, but he now feared for his own sanity because the mental illness that afflicted Rose might be hereditary. He certainly did have a breakdown of sorts in his early twenties. All three major themes of A Streetcar Named Desire reflected his own private terrors which gave the edge to his writing.

Wide Sargasso Sea revision – The fire

Some AO5: Wide Sargasso Sea is a story about ‘human beings claiming, without pity, to own each other, in slavery, marriage or parenthood.’ (Angela Smith)

Creole heiresses were ‘products of an inbred, decadent, expatriate society, resented by the recently freed slaves.’ (Frances Wyndham)

The novel describes the island in a critical moment in which power was being contested between the new colonizers and the liberated slaves.’ (Roberta Grandi)

Antoinette belongs nowhere and belongs to no one.’ (Moira Ferguson

What happens in the fire?

Annette wakes Antoinette

Godfrey, Myra and the other servants have disappeared

Mason tries to calm everyone down

The back of the house is set on fire

Myra has abandoned Pierre to die in the fire

They abandon the house but forget Coco

Coco, on fire, falls to his death

A reminder of key techniques:

Symbolism

Colour symbolism

Pathetic fallacy

Natural imagery

Gothic references

Simile/Metaphor

Sentence variations

Patois dialect/linguistic variations

Aunt Cora threatens the Jamaicans with an eternity in hell

Tia throws a rock at Antoinette

Considering Rhys’ techniques explore how Rhys present the relationship between setting and identity in the following extracts:

How does Rhys present power and conflict?

Extract 1: ‘There is no reason to be alarmed,’ my stepfather was saying as I came in. ‘A handful of drunken negroes.’ He opened the door to the glacis and walked out. ‘What is all this,’ he shouted. ‘What do you want?’ A horrible noise swelled up, like animals howling, but worse. We heard stones falling onto the glacis. He was pale when he came in again, but he tried to smile as he shut and bolted the door. ‘More of them than I thought, and in a nasty mood too. They will repent in the morning. I foresee gifts of tamarinds in syrup and ginger sweets tomorrow.

Extract 2: ‘She left him, she ran away and left him alone to die,’ said my mother, still whispering. So it was all the more dreadful when she began to scream abuse at Mr. Mason, calling him a fool, a cruel stupid fool. ‘I told you,’ she said, ‘I told you what would happen again and again.’ Her voice broke, but she still screamed, ‘You would not listen, you still sneered at me, you grinning hypocrite, you ought not to live either, you know so much, don’t you? Why don’t you go out and ask them to let you go? Say how innocent you are. Say you have always trusted them.’

Extract 3: ‘Mr Mason, his face crimson with heat, seemed to be dragging her along and she was holding back, struggling. I heard him say, ‘It’s impossible, too late now.’ ‘Wants her jewel case?’ Aunt Cora said. ‘Jewel case? Nothing so sensible,’ bawled Mr Mason. ‘She wanted to back for her damned parrot. I won’t allow it.’ She did not answer, only fought him silently, twisting like a cat and showing her teeth. Our parrot was called Coco, a green parrot. He didn’t talk very well, he could say Qui est lá? Qui est lá? And answer himself Ché Coco, Ché Coco. After Mason clipped his wings he grew very bad tempered.

Extract 4: ‘I shut my eyes and waited. Mr Mason stopped swearing and began to pray in a loud pious voice. The prayer ended, ‘May Almighty God defend us.’ And God who is indeed mysterious, who made no sign when they burned Pierre as he slept – not a clap of thunder, not a flash of lightning – mysterious God heard Mr Mason at once and answered him. The yells stopped.

I opened my eyes, everybody was looking up and pointing at Coco on the glacis railings with his feathers alight. He made an effort to fly down but his clipped wings failed him and he fell screeching. He was all on fire.

I began to cry. ‘Don’t look,’ said Aunt Cora. ‘Don’t look.’ She stooped and put her arms around me and I hid my face.

‘Shut your mouth,’ the man said. ‘You mash centipede, mash it, leave one little piece and it grow again … What you think police believe, eh? You, or the white nigger?’

Extract 5:Mr Mason stared at him. He seemed not frightened, but too astounded to speak. Mannie took up the carriage whip but one of the blacker men wrenched it out of his hand, snapped it over his knee and threw it away. ‘Run away black Englishman, like the boy run. Hide in the bushed. It’s better for you.’ It was Aunt Cora who stepped forward and said, ‘The little boy is very badly hurt. He will die if we cannot get help for him.’

The man said, ‘So black and white, they burn the same, eh?’

Continuing today’s lessons: Dreams in Wide Sargasso Sea

Dreams are prevalent in both Charlotte Brontë’s 1847 novel Jane Eyre, and in Jean Rhys’s 1966 postcolonial re-writing of it, Wide Sargasso Sea. In both works, dreams provide glimpses of the repressed or unexpressed emotions of characters. In both novels they also foreshadow events for the benefit of the characters and the reader. Dreams in Wide Sargasso Sea also often contain parallel imagery to dreams of Jane Eyre. The novels, though, have different attitudes towards the distinction between dreams and reality. In Jane Eyre, dreams can drive or reflect waking life, but the two entities remain largely distinct. In Wide Sargasso Sea, dreams leak into the waking world of the narrators, thus giving the novel a dreamlike tone. While dreams in Jane Eyre are tidy and contained, the dreams of Wide Sargasso Sea are jumbled and swamplike.In Jean Rhys’s postcolonial re-writing of Jane Eyre, Wide Sargasso Sea, dreams serve many of the same functions that they serve in the original. The dreams of protagonist Antoinette are often clairvoyant like Jane’s. Both characters also reveal interior selves when dreaming; Jane’s dreams reflect a part of her consciousness that she represses and Antoinette’s dreams reflect a part of her consciousness that she has trouble expressing. Indeed, the functional components of Antoinette’s dreams often parallel those of Jane’s dreams. Jean Rhys was clearly as aware of the various uses of dreams as Charlotte Brontë.

Over the course of the novel, Antoinette has a series of three dreams which she describes as different manifestations of the same dream. These parallel the three dreams Jane Eyre has as she grows increasingly anxious over her marriage. Like Jane’s dreams, they give much insight to Antoinette’s maturing character and provide important foresight into future events in her life.

Antoinette’s first dream takes place in her childhood, the night after her playmate Tia cheats her out of three pennies, steals her dress, and dismisses Antoinette as a “white nigger”.

I dreamed that I was walking in the forest. Not alone. Someone who hated me was with me, out of sight. I could hear heavy footsteps coming closer and though I struggled and screamed, I could not move. I woke crying.

This dream reflects young Antoinette’s undeveloped sense of self-awareness. Its use of past tense suggests that Antoinette is distanced from her dream consciousness. The vagueness of the threat in her dream suggests she does not understand her fears, and reflects her bewilderment and fear at Tia’s rejection of her.

The dream roughly parallels Jane Eyre’s first dream of Rochester. Antoinette’s dream is a sort of inverse of Jane Eyre’s. Jane’s nightmares are based on the receding figure of Rochester, and the inability to reach him. Antoinette’s are based on a malevolent figure approaching her.

As Jane’s dream recurs, so do Antoinette’s. Antoinette has her “bad dream” for the second time at age seventeen, after her stepfather visits her at her serene convent school and tells her he is arranging for suitors to visit her.

Again I have left the house at Coulibri. It is still night and I am walking towards the forest. I am wearing a long dress and thin slippers, so I walk with difficulty, following the man who is with me and holding up the skirt of my dress. It is white and beautiful and I don’t wish to get it soiled. I follow him, sick with fear but I make no effort to save myself; if anyone were to try to save me, I would refuse. This must happen. Now we have reached the forest. We are under the tall dark trees and there is no wind. “Here?” He turns and looks at me, his face black with hatred, and when I see this I begin to cry. He smiles slyly. “Not here, not yet,” he says, and I follow him, weeping. Now I do not try to hold up my dress, it trails in the dirt, my beautiful dress. We are no longer in the forest but in an enclosed garden surrounded by a stone wall and the trees are different trees. I do not know them. There are steps leading upwards. It is too dark to see the wall or the steps, but I know they are there and I think, “It will be when I go up these steps. At the top.” I stumble over my dress and cannot get up. I touch a tree and my arms hold on to it. ‘Here, here.’ But I think I will not go any further. The tree sways and jerks as if it is trying to throw me off. Still I cling and the seconds pass and each one is a thousand years. “Here, in here,” a strange voice said, and the tree stopped swaying and jerking.

Comparing the second dream with the first reveals much about Antoinette’s psychological development. Unlike the first dream, the second occurs in present tense, suggesting that Antoinette has grown closer to her dream consciousness. The plot and context of the second dream have grown more clearer, suggesting greater intelligence and perception. Wheras in the first, Antoinette is merely “walking in the forest,” with “someone who hated me” in the second dream, she walking through the forests around Coulibri in the company of a “man” who is “black with hatred.” The second dream also suggests Antoinette’s budding adolescent sexuality. Antoinette’s attempt to keep her white dress unsoiled, suggests her concern with maintaining sexual purity.

The second dream also foreshadowing much of the troubles Antoinette will face after meeting Rochester. The pure dress represents a wedding dress, and the hateful man represents Rochester. Her reluctance to join the man symbolizes her reluctance to join Rochester in matrimony. Antoinette’s fatalistic resignation to follow the man in the dream, “I make no effort to save myself; if anyone were to try to save me, I would refuse. This must happen,” foreshadows how she “masochistically and insistently lays herself on [the] sexual altar]” of marrying Rochester (O’Connor 186). In her dream, the man orders Antoinette “Here, Here,” and she compiles. Later in the narrative, Rochester sexually subjugates Antoinette, noting, “I watched her die many times. In my way, not in hers”

“We are no longer in the forest but in an enclosed garden,” corresponds to Antoinette’s future relocation to England. The “different trees” are English trees Antoinette has never encountered in the Caribbean. The stone wall is the same wall at Thornfield that Jane Eyre imagines falling from in her second dream of Rochester. The “enclosed garden” and the ascent up the steps prefigure Antoinette’s imprisonment in Rochester’s attic.

Despite their similarities in form and function, Jane Eyre and Wide Sargasso Sea differ in their attitude towards the dichotomy of dreaming and waking. While Jane Eyre maintains distinctions between dreams and reality, dreams blend seamlessly with reality in Wide Sargasso Sea. As a result, the conscious world of Jane Eyre is dualistic, but that of Wide Sargasso Sea is a single jumbled swamp of dreams and waking.

Like Jane, Antoinette is a frequent dreamer. But while Jane’s Victorian upbringing encourages her to minimize her daydreams and isolate her night dreams, Antoinette’s neglected upbringing in the unstable, disorderly post-emancipation Caribbean results in her experiencing waking life as a sort of dream.

Dreams are not just the province of Antoinette’s sleep. Her entire life is emotional rather than logical, surreal rather than realistic, imagistic rather than expository. As Angier writes, “The whole of her life is like a dream, and in particular like her dream” . Observe the dreamlike and detached way Antoinette recalls sewing at the Convent School:

My needle is sticky, and creaks as it goes in and out of the canvas. “My needle is swearing,” I whisper to Louise, who sits next to me. We are cross-stitching silk roses on a pale background. We can colour the roses as we choose and mine are green, blue and purple.

Much of the novel is written in a dreamlike style. Rochester tells Antoinette that Granbois seems “quite unreal and like a dream,” and after he spends some time in the Caribbean, even the parts he narrate take on a dreamlike quality. In the dead of night after receiving a letter from Daniel Cosway that warns of Antoinette’s madness, Rochester goes for a walk in the forest. His description of walking is fluid and primitive and reminiscent of Antoinette’s forest dreams. “I began to walk very quickly, then stopped because the light was different. A green light. I had reached the forest and you cannot mistake the forest. It is hostile. The path was overgrown but it was possible to follow it”.

By the time she has the third installment of her dream, Antoinette has transformed into Bertha Mason, a delusional woman whose only moments of clarity are inspired by flashes of rage. Locked in an attic of Thornfield, Antoinette has lost the ability to distinguish between memory and dream, and thus she removes all barriers between waking and sleeping in Wide Sargasso Sea.

The third dream comes the night after Grace Poole tells Antoinette that she has attacked Richard Mason. Before falling asleep, Antoinette observes her fiery red dress lying on the floor and ponders what she should learn from it, “It was beautiful and it reminded me of something I must do. I will remember I thought. I will remember it quite soon now” (187). This contextualizes her subsequent dream as the revelation of a quest; her dream will tell her what she must do.

In the first part of her dream, she takes the keys from a sleeping Grace Poole, lets herself out of the attic, and floats through the house. As in her first dream, she senses that “someone” is following her (187). When she passes a lamp in the hall, Antoinette remarks “I remember that when I came,” thus shifting from her dream to an episodic memory (187). “There was a door to the right,” it is not clear whether she is narrating from the dream or the memory (187). This passage thus reveals Antoinette’s confusion between dream and memory.

Later in the dream, Antoinette shifts her descriptions between Thornfield and Coulibri without transition, “Suddenly I was in Aunt Cora’s room” (188). In describing first a view from a window at Coulibri and then a set of candles at Thornfield, Antoinette again shifts from memory to dream without distinguishing the two. “I saw the sunlight coming through the window, the tree outside and the shadows of the leaves on the floor, but I saw the wax candles too and I hated them” (188). Again, the narrative maintains no distinction between the states of consciousness.

Antoinette next sets fire to a set of curtains and then a tablecloth in her dream. When she calls to Christophine for help, she believes Christophine answers her call by providing a protective wall of flame. She runs up to the battlements of Thornfield, and gazing in the flames, flashes back through the images of her life.

I saw the grandfather clock and Aunt Cora’s patchwork, all colours, I saw the orchids and the stephanotis and the jasmine and the tree of life in flames. I saw the chandelier and the red carpet downstairs and the bamboos and the tree ferns, the gold ferns and the silver, and the soft green velvet of the moss on the garden wall. I saw my doll’s house and the books and the picture of the Miller’s Daughter. I heard the parrot call as he did when he saw a stranger, Qui est la? Qui est la? and the man who hated me was calling too, Bertha! Bertha! The wind caught my hair and it streamed out like wings. It might bear me up, I thought, if I jumped to those hard stones. But when I looked over the edge I saw the pool at Coulibri. Tia was there. She beckoned to me and when I hesitated, she laughed. I heard her say, You frightened? And I heard the man’s voice, Bertha! Bertha! All this I saw and heard in a fraction of a second. And the sky so red. Someone screamed and I thought Why did I scream? I called “Tia!” and jumped and woke.

Antoinette also exposes several of her interior emotions in this final section. First, she evokes nostalgia. Gazing over the ramparts at Thornfield, she sees the pool at Coulibri. The images of the “the orchids and the stephanotis and the jasmine” and her doll’s house hearken back to her relatively innocent and safe childhood.

Antoinette’s anguish at the corruption of her identity is also present in the final scene of her dream. The image of Coco the parrot jumping from a burning Coulibri parallels that of Antoinette jumping from a burning Thornfield. It suggests that Antoinette feels anguish at Rochester for subjugating her as her stepfather, another Englishman, subjugated Coco by clipping his wings. Antoinette’s inability to recognize her voice as the source of the scream also reflect her loss of identity. Her perception of Rochester’s calls to “Bertha,” an identity he imposed upon Antoinette, suggest Rochester’s role in this loss. While the doll’s house is an image of Antoinette’s childhood, it also suggests another identity Rochester creates for her; that of Marionetta, a doll he can play with.

This violent dream is literalized not in Wide Sargasso Sea, but in Jane Eyre, when Bertha Mason burns Thornfield to the ground and jumps to her death. Antoinette thus remains innocent in Jean Rhys’s novel. While she gets her violent revenge in Jane Eyre, she only dreams of it in Wide Sargasso Sea.

Jane Eyre makes use of dreams as foreshadowing and windows to consciousness. In rewriting Jane Eyre, Jean Rhys preserves these functions, and goes even further by making the whole text of Wide Sargasso Sea a kind of dream. In Jane Eyre, the distinction of dreaming and waking is as strong as Jane’s disposition; in Wide Sargasso Sea it is as feeble as Antoinette’s.